The Society of Saint John the Evangelist is a community of Episcopal monks offering silence and sanctuary in the middle of bustling Harvard Square, Cambridge, MA. They strive to be “men of the moment,” responding to the call of God and the needs of the present world. One of their offerings during Lent was a series of thoughtful, if not provocative, video meditations about what it means to love in life.

One particular meditation contemplated listening as one way to collaborate with God. It asked, “Can you be a listener rather than a savior?” Anywhere from 40 to 80 commenters responded to each meditation daily, forming something of a community over the course of five weeks. Many commenters spoke of “with-standing,” or standing with another, in response to this question.

It called to my mind a case worker in a domestic violence shelter where I volunteered fresh out of college. Clients came to her with real, seemingly insurmountable predicaments. Obstacles heaped upon obstacles were dumped at her feet for fixing. I wish I had words to convey the relief—the true blessing of grace—that would come over a client’s face when the case worker said, “Boy, that’s a tough one. I don’t know what we’re going to do about that. But, together, we will figure it out.” No answer, no remedy, no solution would have put people in crisis at ease the way she did by simply acknowledging the severity and letting them know she was in their corner.

That also put me at ease. As a naive 22 year old, I was conscious of what I lacked. What wisdom do I have to offer? Certainly I didn’t have any solutions for these inexorable real life problems. Confronting challenges we’re ill-equipped to handle is not the unique province of 22 year olds. We all face situations in life that seem bigger than we are. A neighbor pulled me over last week when I was out running. She’s the live-in care giver for my 90-something neighbor. He’s in decline, and she needed to talk. She has fear, uncertainty and doubt about the future and her ability to influence it.

We talked about loaves and fishes. Sometimes what we have to offer is woefully inadequate for the situation at hand. In the bible story, however, Jesus doesn’t ask his disciples to have enough. He asked them what they had. It suggests God doesn’t ask us to have enough, either. He merely asks us to give the inadequate bits we have so that he can do the miracle of making it enough.

Why do we resist? Are we afraid we’ll look stupid with our meager offering? Or are we afraid we won’t have enough for ourselves? Do we fear the failure that seems probable? Or do we fear a miracle even more? This last one intrigues me. It suggests we’re so attached to the notion we’re in control, we don’t make room for God’s power.

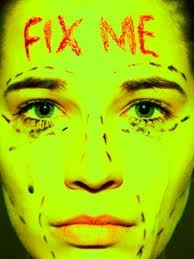

Join the conversation. To be heard, not to be fixed—is this what people really crave? Is this what God does?

Copyright 2014 Stephanie Walker All rights reserved. Visit www.AcrossTraditions.com.